A Snippet from Undercut, my novel about logging in Tahoe

For ten years, I’ve kept this book very close to my chest. Maybe it’s time I share something?

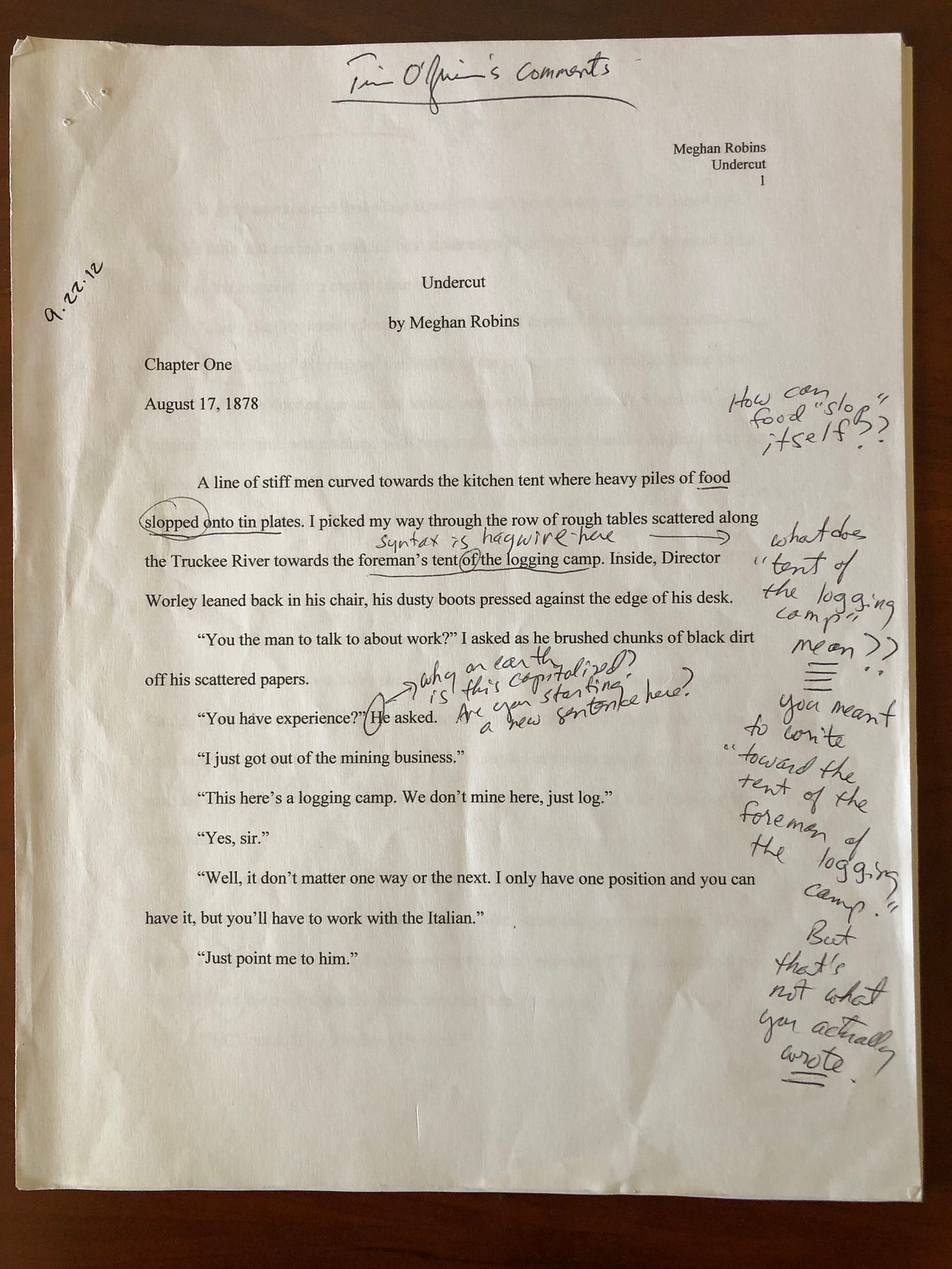

The first chapter I ever wrote got me into grad school, where I had the surreal experience of having Tim O’Brien (famous for writing The Things They Carried and others) line edit my chapter. That’s one amazing benefit of earning your MFA: having super famous writers ask questions about your story!

Except, I was young. This chapter was the first serious piece of fiction I’d written. Tim O’Brien’s comments were brutal and accurate. He used a lot of exclamation points, triple underlined my grammatical follies, questioned my syntax. For better or worse, his comments occurred so early in my writing process that he completely altered the shape of my novel.

His questions: What’s at stake for the narrator? What does he want? What does he need? Why is he here? are all good questions. Questions I now realize get answered as the writer keeps writing. Unless you are a diligent outliner (I am not), these answers sort of take shape as you go. When I think back on that workshop, I realize my chapter, while rough, was appropriately raising questions that served as interesting hooks. Yes, I had a lot of work to do, but also, the reader wanted to know more.

This scene still exists in my novel. It’s actually a core piece, but it has changed. Namely, I’ve shifted the entire book from 1st person to 3rd person, an arduous undertaking but it unshackled my point of view from writing as one Euro-American man to allowing me to explore other voices.

Sketching My Characters to Life

One of my proudest delay tactics (writers do avoid writing) includes asking my friend, the talented artist Christina Schueler, to sketch some of my characters. What a pleasure it is to see them come to life! This collaborative effort included my sharing character descriptions, Christina drawing a version, my commenting, her adjusting, and voilà!

Below you’ll see two of the first characters I ever wrote for Undercut: Joshua, my narrator turned 3rd person protagonist, and Giuseppe whose illusive ways are why writers say silly things like, “Why won’t my character just do what I want?!” Well, I get it. Giuseppe is one of those frustrating and fascinating characters for me. It’s weird. But Christina’s rendition of him pretty much says it all. Thank you, Christina!

Without further ado, I am sharing with you an actual excerpt from my novel-in-progress:

Worely’s Logging Camp, Truckee River, 1859

The sun drifted west, replacing calm air with a steady breeze. Seven men emerged from across the river. From a crate marked explosives, they took a plate, cup and spoon, then held steady while Maureen ladled stew. Each man was allotted one roll, puffed like a downy hen. At the table, they got straight to eating. Joshua had never seen so many men sit quietly together. When he reached for a plate, Maureen tsked. “You eat only after you work. There’s Worely.” She nodded at a tall, yellow-haired man walking toward the only other tent in camp.

“He doesn’t eat?” Joshua said, acutely aware that three plates and a dozen rolls remained.

“He writes his numbers first. And I never run out of food for my boys. Go on. Now’s the time to ask about staying.”

Joshua skirted the feasting men hunched over their plates and wondered if they could see him at all. Or was he so thin a person, so frail a personality, that these rough and solid men could not feel his presence. Since he was a boy, he understood his worth to be less than: less than smart, less than charming, less than skilled, less than worthy of his brothers’ secrets. He was their tolerable tag-along, nothing more. The only thing he and Stanley had in common was their admiration for Robert. That Robert loved them both was certain; he was their glue, their common bind. But where was he now? Murdered, thought Joshua and the word tangled his brain. Instead of anger welling inside him, Joshua felt disgust, and humiliation that manifested as nausea. He’d left Robert laying there on the ground, maybe still warm had he dared touch him. What would become of him with Robert gone? Joshua shook his head. He hadn’t even buried him. There had been no reason, no gunfight, no greater threat than his own timidity and fear that made him run. The truth was, when faced with a terrible calamity, Joshua now knew he was the kind of man who slithered into the night while his brother lay unburied, without ceremony. For all he knew, Stanley had suffered the same fate and was lying dead in the bushes not far off. How could he leave? It was the same reason he was unseen by these men here. Every step and every breath made him thinner, less of a person. He was nobody, quickly becoming nothing. Without his brothers, he had even less chance of succeeding in the world, of becoming anything noteworthy. A few steps more when he reached Worely’s tent, his entire existence was in question.

“What do you want?” Worely asked the shadow at his door, bending over his desk so only his cowlick was visible. Greasy yellow strands draped across his face like a curtain. Worely scribbled his remaining numbers then tucked the red, leather notebook into his vest.

Joshua stepped forward. “You the man to talk to about work?”

Worely crossed his arms and spit a foamy white bead that pearled against the packed dirt floor. “Cutting season’s begun already. I don’t take men so late in July.”

“I have my own horse,” Joshua offered.

Worely combed his hair with all ten fingers. A crease where his hat blocked sun and dirt give him a look of perpetual concern.

“Grady sent me upriver,” Joshua said. “Says he’s ready for orders.”

Worely picked pitch off his thumb. “I recognize you. You got family out this way?”

“No sir. John Grady sent me. Says his outpost is ready for business.”

“I heard you.” Worely cut a palm through the air. “You should’ve turned east at the confluence. Go back a full day’s ride. Mills there take just about anybody. Tell Grady I’m much obliged, but not for the likes of you.”

“My pa’s a timber man,” Joshua managed, feeling one more rejection might split his soul completely.

“Did you bring him?” Worely lurched from his desk. “I don’t give a damn who you are or where you’re from. You’re too thin. Twitchy. Something don’t feel right.”

Despite weeks of working with Grady, Joshua was too thin. Distress and anguish had eaten him up. Any eagerness to stay wasn’t ambition, just physical hunger. He wished Maureen would walk over and hug him, wrap him up her big doughy arms and say everything was going to be okay. He was no match for this place. He turned to leave.

Worely followed him out the door, staring across his men. “Why here? Of all places, my operation’s the farthest from the mines. Makes no sense to some, but I have a plan. I’ve seen men like you before. I don’t believe you’ve arrived here on your own volition, son.”

“I just need the work, sir. I didn’t take well to mining.”

Across the yard, four men squeezed side by side were eating ravenously at one table. Maureen bustled over their shoulders pouring coffee from a kettle. The only sounds were tin slamming wood, forks scratching plates, and the river flowing beside them. For the first time, Joshua noticed a second table sat empty. Worely fingered his hair in rapid succession: once, twice, three times. When he rested his thick arms by his sides, they bowed uncomfortably. “Seven’s a bad number,” he said. “If I count the doctor, we’re at eight men. This here’s a logging camp. We don’t mine. Just log. You understand?”

“Yes, sir.”

From the river strode a barrel-chested man and a boy beside him. Maureen hurried to her ladle to serve them, affectionately ruffling the boy’s hair as he passed.

Worely’s demeanor stiffened. “That there’s Giuseppe and his son.” Giuseppe was taller than Maureen by two hands and thick as the pot before him. His dark wool overshirt stretched over muscular shoulders; arms that never relaxed. Black curls burst from his collar and beneath his wide-brimmed hat, shadowing high cheekbones and a broad nose. The boy, maybe fourteen, was tall and thin with thick, black hair like his father’s. The pair carried equally full plates to the empty table and sat with plenty of elbow room. Quickly, quietly, they shoveled food into their mouths. Every once in a while, Giuseppe squeezed foreign words past full cheeks and the boy nodded.

Worely turned to Joshua, awaiting an answer without asking any question. “I’d feel better with eight. Eight’s the better number.” He let out an exasperated exhale. “You can have the job,” he said. “But you have to work with the Italian.”

Foolishly Joshua’s heart swelled, feeling accepted. This was exactly what he needed. He had a job. More importantly, he had someplace to be for a while. Worely plucked the topmost ax from an unkempt crate of tools and thrust it toward Joshua.

“What’s your name, son?”

Thumbing the dull blade, Joshua smiled in spite of himself. “Joshua, sir.” The wooden handle wobbled in the iron socket but fit solidly in his palms, assuring his body would not float off in the summer breeze after all.

“You look strung out like the rest. Keep to yourself. Don’t cause trouble. Strangers agitate the men. This is my operation. I choose who stays and what goes. By the looks of you, I’d rather make Maureen my number eight, but she’s too valuable down here and I need someone up there with Giuseppe. Something’s got him distracted and I don’t intend to lose my best faller. So, you watch him. That’s your job.”

He slapped Joshua hard on the back. “I’ll take care of your horse. Pay you a dollar extra a week to use him. You only get paid for what you haul in. We don’t get paid till the end of cutting season. Good luck, son.”

Joshua carried his ax toward Giuseppe. The light in the sky faded, casting the canyon into cool shadow. Soon it would be dark, and Joshua still hadn’t eaten. His stomach, he feared, was the loudest thing about him.

“Go ahead,” one of the loggers said, “introduce yourself.” A low rumble of laughter emanated from the table.

Joshua took another step and a boney hand clamped down on his shoulder. A tall slender man with wispy hair whom he’d not seen before pulled him backward with more force than expected. “You must be lost, my boy.”

“I’ve just been hired on.”

“You sure as hell act lost. What are you thinking, giving these men a show with their meal? No one disturbs Giuseppe and Felipe’s time together. Although on occasion, I am permitted to join.” The man’s expression shifted from furrowed to beaming.

“I just meant to introduce myself.” Joshua tried to wriggle free, but the man’s grip was unexpectedly strong.

“I’m sure you did.” He laughed with blue eyes and eyebrows that curled up like caterpillars. “I’ve lost my manners in these damn mountains. Doctor Blask, Doctor Jonathan Blask. I’m the doctor round these parts.”

Joshua yanked his arm away, pausing at the doctor’s repetition. “I’m tired of people calling me son. I’m here to work and I mean to do so.”

Doctor Blask rubbed his chin and lowered his voice, his thin frame towering. “Well, son, I’ve heard Worely say a dozen times that there’s one job left and that’s with the Italian. Is that what he told you? Most men don’t last long on the mountain. But at least they get up there. No one’s foolish enough to go right up and kick a sleeping bull.”

Three paces away, Giuseppe tore chunks of bread with giant hands, elbows resting on rough timber as if relieving his shoulders of some terrible weight. His back was broad and tapered at the waist with a belt that seemed long enough to loop Joshua’s frame twice. He soaked a bite of bread in stew before swallowing and nodding at something Felipe was saying.

Joshua spoke quietly. “I had no intention of kicking him.”

The doctor’s frown pulled up into a smile. “Of course not, son. My word, what a silly thought!” He squeezed Joshua’s forearm and looked at him closely before trotting toward Maureen, saying, “Come along, did you get any food?”

Worely was back inside his tent, so Joshua followed the tall, lanky man whose steps looked more like skips and wondered if there were two people inside his one brain. Maureen handed Joshua a shallow serving—no bread. Doctor Blask’s plate was filled to the brim, a golden roll plopped on top. He leaned close and said, “Lovely as ever, my dear.” Maureen blushed before turning on Joshua. “That meal will cost you. You don’t get fed just ‘cause you’re here.”

Joshua nodded. The smell of stew with onion and carrot and salt, duck not rabbit, wafted so sweetly he fought the impulse to weep. Where Maureen had gotten such ingredients this deep in the mountains, he could not guess.

When the men finished eating, they washed their plates in the river before depositing them into the crate. Maureen glowed with every “thank you ma’am” and “delicious as ever.” Requisite praise to ensure a full helping the next day. While some men carted water to the pot for cleaning, others pilfered coals from Maureen’s cooking fire to another circle of stones. Chores were done with little instruction and fewer words. They retrieved bed rolls, lit pipes or tobacco papers or just lay down by the warmth of the fire. All was done quietly and efficiently. Six men, one cook, a foreman and a doctor, all accustomed to one another’s habits.

Unable to muster the courage to cozy up around the fire, Joshua thanked Maureen, returned his clean plate and skirted the aspen grove to find Samson grazing near the river. Unsaddled, Samson’s brown flank was matted with a sore and Joshua worried how he’d do as a work horse.

“Just for a few weeks,” Joshua said. “Till I toughen up and figure out what to do. Then we’ll get out of here.” He shook Samson’s blanket and curled beside some moon-glistening granite. Alone for the first time in a long time, he hugged the black hallow of his chest. Such emptiness would be hard to fill. Without Robert, without Stanley, he had only himself to comfort. And who he was becoming was not entirely pleasant. For a long while, he lay wide-eyed in the aspens, the river gurgling beside him, stars shimmering above. Alone in the woods, he had nowhere to hide, and the reality of what he’d done was haunting him.

The whole time I read this I kept thinking, damn, I'm going to be friends with an award-winning author. Thanks for being so transparent about the writing process and the transformative power of studying story craft. This is going to be something epic.