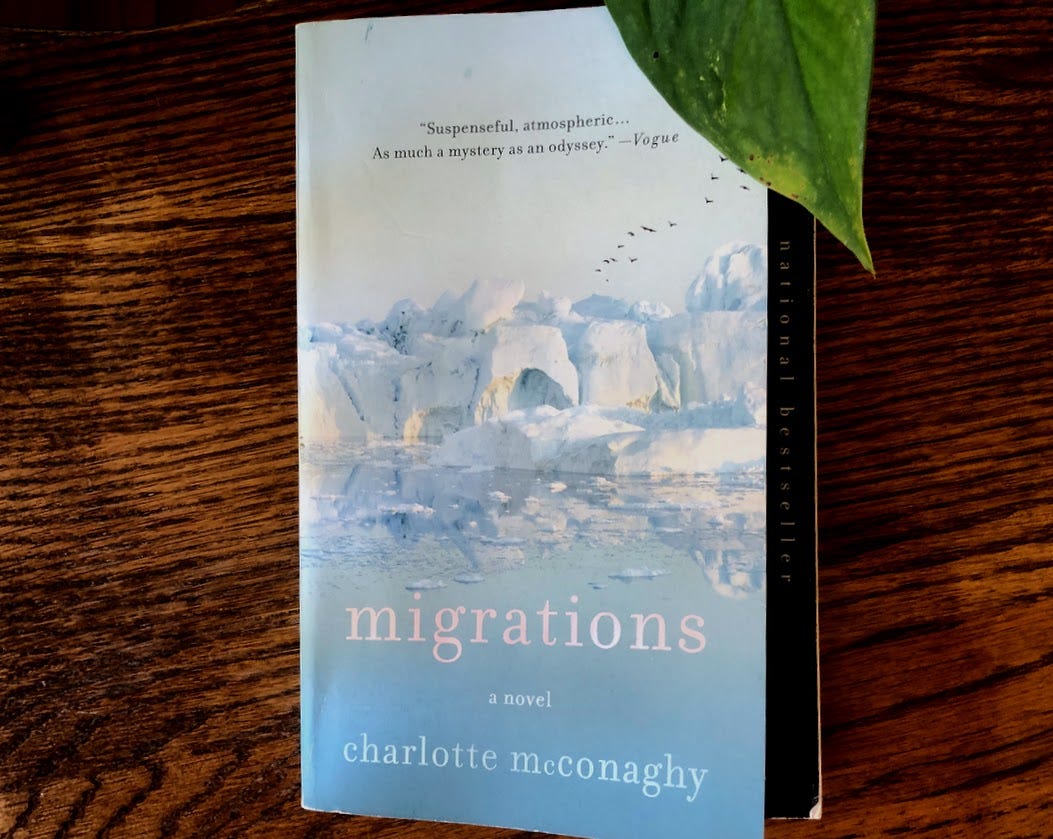

Book Review: Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy

A slight departure from my regular stuff, but here's a book review from a writer’s perspective...

Migrations by Charlotte McConaghy is a seafaring adventure with well-developed characters and tight composition. While some rebuke McConaghy’s lack of fully committing to her dystopian future, claiming this is a book about climate change, I argue it’s a book about recovery.

Set in the not-so-distant future where humanity’s greed and failure to mitigate climate change result in the extinction of most animal species, Migrations follows a woman’s drive to seek the last Arctic terns by boarding a soon-to-be outlawed fishing vessel on what could be their last commercial catch. Here’s my review:

Word Choice: Concise Writing

On a sentence level, McConaghy’s writing is concise but not dense. For a reader studying writing, this distinction is important. Dense writing is when each word holds so much meaning the mind cannot easily tie all concepts together as fast as the eye reads. Each word is so loaded one might read a sentence then think, Wait, what did I just read? And pour over it again. This disrupts the flow and reminds readers they are holding a book written by an author, rather than being immersed in the fictional world.

Concise writing, on the other hand, is placing the right words together so each word is achieving more than it, alone, is capable. It’s editing away unnecessary words. Choosing the strongest verbs. Using adverbs sparingly (eh? 😉). Letting each word do plenty of work. Poets are masters of this. McConaghy does a good job too. For example (bolding is mine):

“We don’t move, but outside the world is still shifting and breathing and living. The moon lopes her path over our heads. I live in his words, and in the vastness of his contradictions.”

Strong verbs pull the imagery along efficiently, and McConaghy has a habit of combining nouns with unlikely verbs: “I live in his words…” A literal impossibility, but oh how efficiently this phrase conveys the depths of their relationship. There are thousands of ways she could have written their love, but “I live in his words” shows how deeply invested the narrator is. The all-encompassing “living” tucked inside seemingly small “words.” A perfect pairing of unexpected verb + noun.

Pacing: Short Chapters

Short chapters are something I’m seeing more in recently published novels (All the Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr, Those We Thought We Knew by David Joy to name a few)—a symptom of our short attention spans, perhaps. In Migrations, McConaghy stacks bite-sized moments, maybe 800-2000 words, switching between ocean-crossing adventures and the narrator’s flashbacks—the past and present.

As a writing device, short chapters avoid unwieldy transitions. Let the chapter break pause the reader’s mind. They’ll understand that Character got from A to B during the white space where “Chapter 5” is written as the header. Short chapters are also effective because readers think, eh just one more and can never put the book down.

My own novel has lengthier chapters, and I wonder how the reader will tolerate them. I know that my purpose in writing longer chapters, for this novel at least, is to keep the reader invested in one storyline at a time. I’m flipping between entire worldviews and want my readers to feel each world deeply before moving along to the next. I hope my pacing creates an aching to return to whichever world you just left, and thus keep the reader intrigued.

Structure: Flashbacks

The beginning if Migrations does what beginnings ought to do: raise questions. But more questions are raised than answered and with so many early flashbacks, I can feel the author’s hand—a red flag for writers. The narrator knows what happens next, so does the author, but the chapter stops short and I, the reader, can feel the author withholding (again taking me out of this fictional world).

Although many books (including this one) get criticized for this, it is actually the purpose of a non-linear structure. Either a novel is written linearly, start to finish, or there’s the use of flashbacks, jolting readers away from the present to some previous moment that informs the scene we just left. Critics of Migrations say McConaghy used this devise too much. But I kept reading and I’m glad I did.

A quarter in, I’d forgiven McConaghy for her withholding because 1) I’d learned the structure, 2) I’d accepted it, and 3) both the present and flashback storylines become compelling enough that I wanted to find their links. As a writer, this is something worth studying: how structure can strategically complicate an otherwise simple storyline.

In the present timeline, the narrator Franny Stone is seeking a vessel to follow the Arctic terns to Antarctica. The flashbacks jump from four to twelve years ago and explain her confusing past. Why is she so self-destructive? Where is her husband? Why does she always leave? The equal space on the page dedicated to flashbacks and the present create a structural tension the reader wants to figure out. Once you learn the structure (short chapters with cliffhanger endings) and you forgive the author for doing this, you trust her to reveal the connections.

The present timeline will answer the big question of: Will she make it to Antarctica? The flashbacks reveal why she’s there in the first place.

As a reader interested in the craft of writing, it’s good to ask: Would this story be as compelling if written linearly? Is McConaghy’s choice of flipping between past and present the only thing giving this novel emotional weight?

By the end, we finally learn what happened in the beginning. And, I’ll argue, it was purely a structural device that causes this tension. Had the chapters been organized linearly (in order in which they happen) I’m not sure the novel would be as compelling. (Another example of a book relying heavily on structural tension is Idaho by Emily Ruskovish).

Yes, I Recommend

Overall, I like this novel. I think it works. It captures the perfect combination of physical action-adventure with deep psychological purpose. It’s about one woman who cannot outrun her past, her genetics, and an irreversible crime that she believes can only be resolved by reaching Antarctica. (Forewarning: the novel does contain descriptions of physical and self-harm.) I kept reading because the writing, on a sentence level, was beautiful and I wanted to know why Franny was doing what she was doing.

Whatever the criticisms, this is a book worth reading and worth studying, both for the quality of the writing and the structure the author chose. The culmination of past and present leaves readers emotionally raw and reverberating.

Based on a scale I just made up, I give Migrations an 8/10. Happy reading!